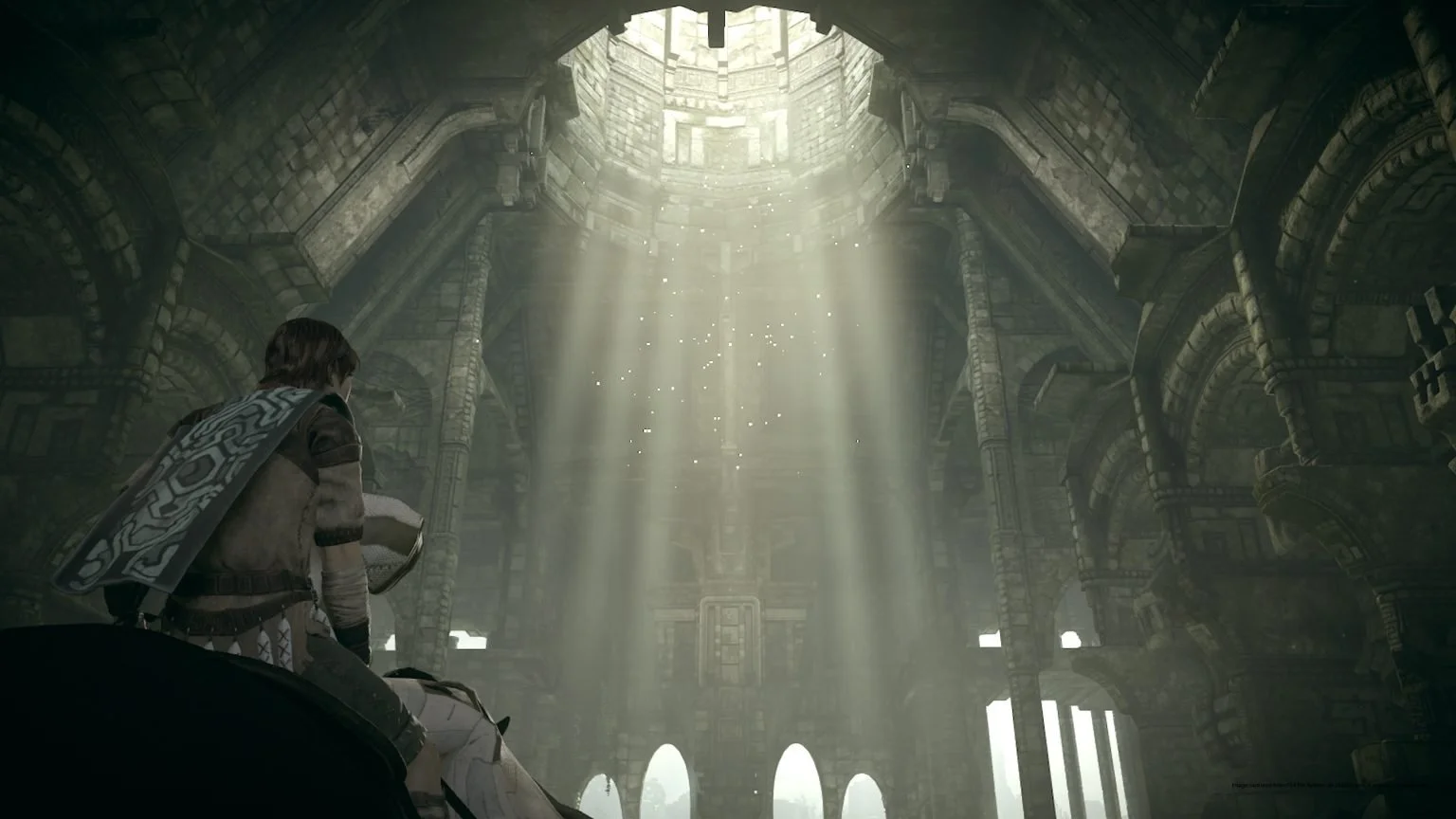

First Frames - Shadow of the Colossus

“Shadow of the colossus is a game that defies explanation.”

Are video games art?

It’s a question that never seems to fully die out. Just when you think people have stopped caring about whether video games hold artistic value, a game like The Last of Us comes out and nerds storm the internet flooding subreddits with arguments and examples.

The “video games as art” debate has raged on since the inception of the medium itself. Even when games were no more than brightly colored pixels dancing on a CRT TV, folks had no idea what to make of such an orthodox form of entertainment. Thus, books, video essays, and furious Internet rants have persisted for decades.

I myself didn’t think much of the question. In fact, I don’t think I even need to answer it.

Shadow of the Colossus did that for me years ago.

Shadow of the Colossus is a game that defies explanation. It released in 2005 at the tail end of the PS2’s life-span but went on to be a defining feature of the PS3. It only sold a modest number of units but is frequently cited as one of the greatest games of all time. It’s from the same team that made Knack.

I didn’t know much going into the game. I knew it was important (I jokingly referred to it as “nerd homework”), I knew you climbed big monsters, and that’s about it. In fact, the only reason I chose to play it at that moment was because it only took a measly 4 hours to beat. I had just finished Persona 5, a whopping 92 hours of gameplay, and needed a palate cleanser. So, nearly blind, I sat down and booted up the PS4 remake of Shadow of the Colossus for the first time ever.

Right away, the game sets itself apart. A sweeping cutscene sets up the premise of the story: a boy named Wander is carrying an unconscious girl (named Mono) through forest and mountain to a temple in a forbidden land. He has come to this temple seeking to resurrect the girl – at any cost. A disembodied voice named Dormin, who the boy has heard can resurrect the dead, instructs him to kill 16 colossi that roam the country. Only then will Dormin revive the girl - but her new life will come at a terrible price.

And just like that, the game begins. Instantly, Shadow of the Colossus feels different. The HUD is minimalistic, and you control Wander, the protagonist, with just a few simple buttons. I have an objective, so I set off toward the first colossus, guided only by the light of my sword. There’s no run button available, so I’m forced to meander past trees and through grass to reach the first colossus. It takes a moment for me to do so. The game’s heavy emphasis on travel and nature is unmistakable, as it takes extended periods of riding your trusty steed Agro to reach each colossus. There’s no buildings, only ruins, and no people - just stretches of land. It’s silent, and slow, and stunning.

“There’s no buildings, only ruins, and no people - just stretches of land.”

As I encounter the first colossus, the meat of the gameplay reveals itself. First, I have to observe the beast and find a weak point somewhere on the body. Then I need to scale the giant somehow. Each of the 16 colossi require a different method to reach their weak point. The fights feel less like brushes with death and more like quiet observing and puzzle-solving. And you take minimal damage from the Colossus-almost as if they’re not trying to hurt you-so the game encourages you to breathe, stop and think. It’s a fascinating approach to combat that stands in stark opposition to other gritty, intense action games of the 2000’s.

As I plunge my sword into the beast’s head one final time, there’s no fanfare of victory; rather, melancholy strings and piano accompany the death. I stand, unwavering, until strands of shadow from the corpse kill me unceremoniously. I re-emerge in the temple of resurrection with a new target, and off I go again.

This is the central conceit of the game, and while it takes time to learn to be patient as I navigate towards my next target, this forced patience allows me to fully appreciate the atmosphere of Shadow of the Colossus.

There’s an eerie undercurrent of sadness to the whole experience. The world is empty, hauntingly so, save for yourself and the colossi - magnificent creatures which only attack you if provoked. It’s beautiful, but makes you feel as though you’re an intruder, coming into the homes of these creatures and felling them mercilessly. While swelling orchestras build under each attempt at scaling and killing the different colossi, they leave a bitter aftertaste.

By the time I’ve killed the 15th colossus, I’m fully questioning whether these beasts deserve to die. I’m acting as the protagonist but I’m only doing this because the game told me to. If I kill the monsters, the girl is saved. I have no personal connection to Mono-we never see exactly why Wander cares so much for her or what their relationship is-so I have no stake in the game. But I’m curious to see how it will all play out, so I ride to the 16th and final colossus.

The final boss is an absolute skyscraper, implementing every puzzle you’ve solved and every trick you’ve learned from the previous colossi. As I’m scaling this mountainous creature, rain pelting around me, the magnitude of the game continues to settle in. Many games strive to be considered “epic”; that feeling of grandeur and adventure is a difficult one to instill. Shadow of the Colossus does it effortlessly.

The soundtrack is one of the most beloved in gaming for good reason, as violent swells of violins and thundering drums capture the sensation of the towering colossi better than most movies could. Though the visuals are slightly dated, having been updated from 2005, the PS4 remake does the game wonders. It looks and sounds like an entirely different world. As I cling to the beast’s hand, hundreds of feet up from the ground below, this is where I first consider that this game truly is art. It might not be art in the same sense of Monet, Beethoven, or Warhol, but it’s art nonetheless. Art is meant to inspire awe, after all, and nothing is more awe-inspiring than this. I sink my blade into the colossus and as it topples to the ground, I think I finally understand what all the hype is about.

Then the final cutscene plays.

“Many games strive to be considered “epic”. Shadow of the Colossus does it effortlessly.”

While the game’s story has been minimal, sprinkled in are small cutscenes of people riding to the temple of resurrection where you undertook your quest. Now, returning to the temple after the final colossus’ death, we find out who they were looking for: you.

Remember Dormin? The voice who has instructed us to kill the colossi in return for the life of Mono? That voice belongs to an ancient demon, who has been trapped for centuries. His body was destroyed long ago and split into sixteen parts…parts that are, in fact, the colossi we’ve been tricked into hunting this whole time. The group of people were storming here to stop us from completing the ritual, but it is too late. Dormin returns, using a new body - our body - as a vessel. Wander, now possessed by this ancient demon, rises as a shambling corpse. He hopelessly stumbles towards the still sleeping form of Mono before being shot down by the panicked men around him. Dormin is sealed away once more. The spell works, and though we see Mono at last revived, she is trapped in the forbidden land, sealed away by the men who fear Dormin’s power.

The rug of heroism has been pulled out from under me. Shadow of the Colossus is not a story of triumph. It is a tragedy.

This entire time, I’ve journeyed as the supposed champion of this world. In reality, that tinge of guilt I felt marking every landscape and killing blow throughout my playthrough was entirely intentional. I was tricked in a way that seems obvious now but is impressive regardless.

At this point, as the credits roll, I set down my controller and let out a breath I didn’t know I was holding. I’d played games that had blown me away, many a time, but none in such a simple and effective way. It was heartbreaking, and beautiful, and concise. It was a cautionary tale, asking me how far I would go to save someone before considering the consequences. It’s a message I’ve heard before, but never in a way that immersed me so wholly in the world itself.

I now think that some video games are art. Whether through spectacle, or narrative, or gameplay, or some masterful combination of the three, video games can in fact achieve that lauded status of “artistic genius.” I learned that the best way possible: through a four-hour journey that continually knocked me off my feet.

If you have a chance, play Shadow of the Colossus. You’ll be glad you did.